Native species of trees and the wood produced by these trees are divided into two botanical classes-hardwoods, which have broad leaves, and softwood, which have needle-like or scale-like leaves. This botanical classification is sometimes confusing, because there is no direct correlation between it and the hardness or softness of the wood. Generally, hardwoods are more dense than softwoods, but some hardwoods are softer than many softwoods.

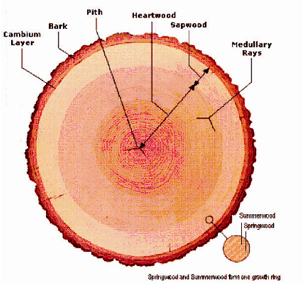

The cross section of a tree shows the following well defined features in succession from the outside to the center: (1) bark and cambium layer; (2) wood, which in most species is clearly differentiated into sapwood and heartwood; and (3) pith, the small central core. The pith and bark are excluded from finished lumber.

Most branches originate at the pith, and their bases are inter-grown with the wood of the trunk as long as they are alive. These living branch bases constitute ingrown or tight knots. After the branches die, their bases continue to be surrounded by the wood of the growing trunk and thus loose or encased knots are formed. After the dead branches fall off, the studs become overgrown and subsequently clear wood is formed. FAS and Selected grades of hard-woods are cut from the outside part of the log. Therefore, FAS and Select grades will have more sapwood than the common grades. All growth in either diameter or length takes place in wood already formed; new growth is purely the addition of new cells, not the further development of existing cells. The cambium layer is the only growing part of the tree.

Most species grown in temperate climates (having four seasons yearly) produce well defined annual growth rings, which are formed by the difference in density and color between wood formed early and wood formed late in the growing season. The inner part of the growth ring formed first is called "springs wood," and the outer part formed later in the growing season is called "summer wood." Spring wood is characterized by cells having relatively large cavities and thin walls. Summer wood cells have smaller cavities and thicker walls, and consequently are more dense than spring wood. The growth rings, when exposed by conventional methods of sawing, provide the grain or characteristic pattern of the wood. The distinguishing features of the various species are thereby enhanced by differences in growth ring formation. By counting the growth rings you can determine a trees age as one ring is formed each year.

Sapwood contains living cells and performs an active role in the life processes of the tree. It is located next to the cambium and functions in sap conduction and storage of food. Sapwoods size varies by species and where the tree is growing. Sapwood is not weather resistant in any species.

Heartwood consists of inactive cells formed by changes in the living cells of the inner sapwood rings, presumably after their use for sap conduction and other life processes of the tree have largely ceased. The cell cavities of heartwood may also contain deposits of various materials that frequently provide a much darker color. All heartwood, however, is not darker. The infiltrations of material deposited in the cells of heartwood usually make lumber cut form heartwood more durable when exposed to weather.

Medullary rays extend radially from the pith of the pith of the log toward the circumference. The rays serve primarily to store food and transport it horizontally. They vary in height from a few cells in some species to four or more inches in the oaks, and produce the flake effect common to the quarter sawn lumber in these species.

|